ORTHS NURSERY: KEEPING THE LEGACY ALIVE

Initially, business for the two nurserymen had been slow and frsutrating. They tended the sprouts, and began growing vegetables, expecting good revenue at the Croydon and Dandenong markets. However, things did not take off as quickly as they had anticipated. This saw a young and impatient Reinhold leave his father and their property, in hope of a more profitable venture.

During Reinhold's five year hiatus, Johannes had continued to work diligently, becoming well acquainted with the other vegetable vendors.

In 1956, when Reinhold returned to the Ferntree Gully farm, he was informed of an offer almost too good to be true. A stall at the Victoria Market was about to become available, and they were being offered the spot.

Tragically, Johannes Orth did not have long to enjoy the fruits of his labour. He passed away in 1958, after a gallbladder operation, and consequent infection.

By this time my Opa had met the woman he was to marry, my Oma, Gusti Orth, and together they continued toiling on the farm. The Victoria Market had brought with it fantastic new business, and reignited my Opa's passion for horticulture.

In 1975, with two children in tow, the pair upgraded to a bigger block of land in Coldstream, where they still reside. Though they are both retired now the Orth Nursery lives on, and has been taken over by my aunt and uncle, who have added vineyards and ventured into wine making.

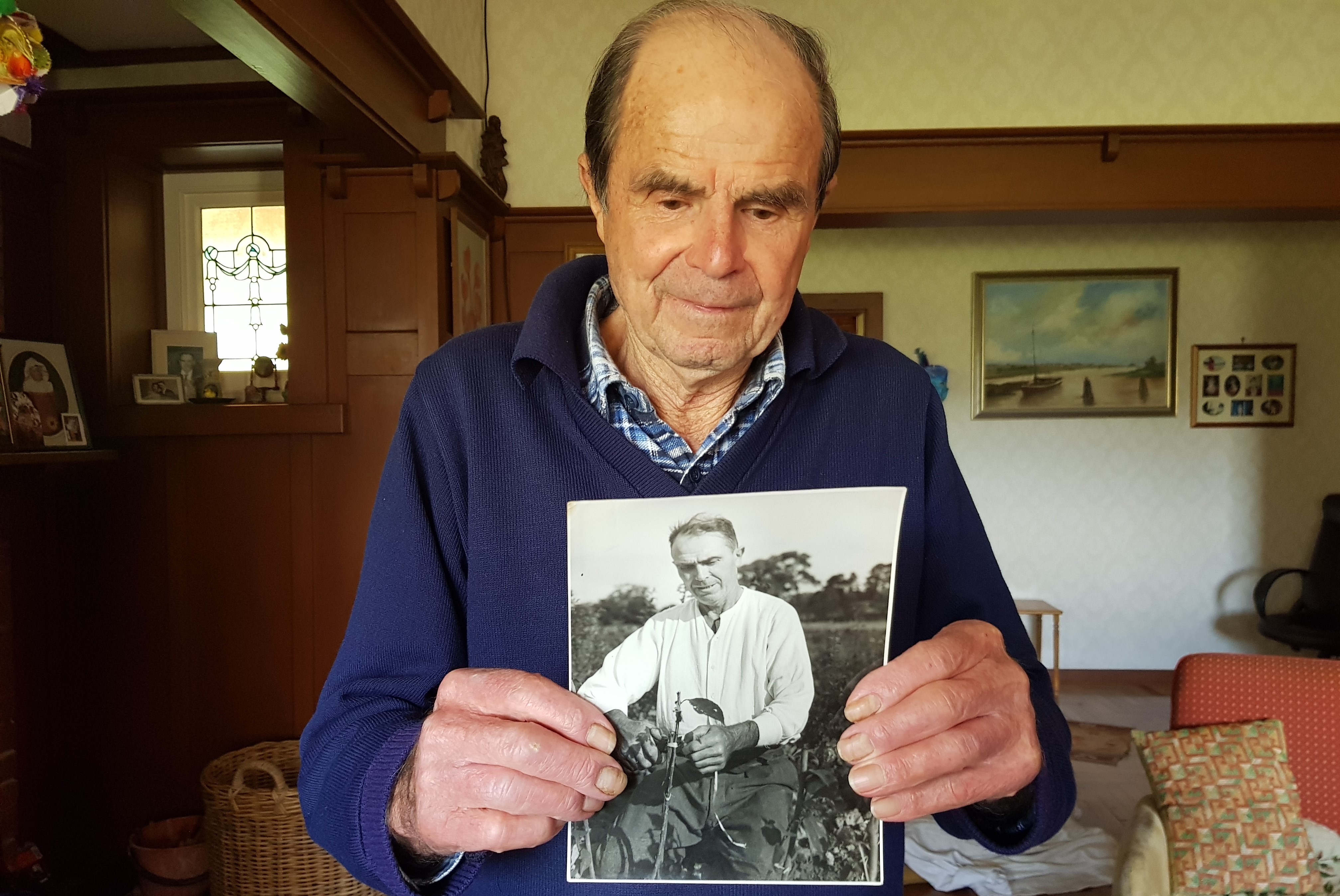

Despite his age, my Opa has never abandoned his love for plants. He still spends everyday out in his veggie patch; planting and weeding, sowing and harvesting. This love for horticulture is an unwavering conenction to not only his father, but also his people and his homeland

; a connection to his roots.